SerenityOS's Build System In-Depth, Part 1: Makefile City

The build system for the Serenity Operating System looks daunting at first glace. Let’s take a look under the hood :^)

Serenity is a complex software project. As on operating system monorepo, it has patches for the GNU and Clang compiler toolchains to target its Userspace and C library implementations, a bare metal Kernel to build, dozens of Userspace libraries, a runtime dynamic loader, and assorted command line utilities and GUI applications. In terms of scope, serenity could be compared to a *BSD project like FreeBSD, with a desktop environment and “full” set of GUI applications all built out of one monorepo, from scratch, in C++.

As the project has expanded its scope over the last 3 and a half years, it has outgrown its build system a few times. The current build system architecture tries to make the build as portable as possible to as many host operating systems and distributions as possible.

Before we get into the details of the current build system and the problems it tries to solve, however, some history is in order. How has the build system evolved over time?

This series will go over the concepts, history, and rationale behind each phase of the Serenity operating system’s build system design and implementation.

- Part 1: Makefile City (this post)

- Part 2: CMake Metropolis

- Part 3: Superbuild Metro Area

In the beginning: Makefiles and shell scripts

Like many Unix-oriented software projects, the original build system for serenity was a maze of Makefiles, and some bespoke scripts to drive them.

When Andreas published his first monthly update video on March 30, 2019, the build was very old school. As the project was a bit difficult to build at that time, let’s take a look at how the build looked after a toolchain build helper script was added, all the way back in pull request number 8! However, the build script still had a few bugs in it after that, so let’s move forward another few months until we get to a script that actually works from a fresh checkout (almost).

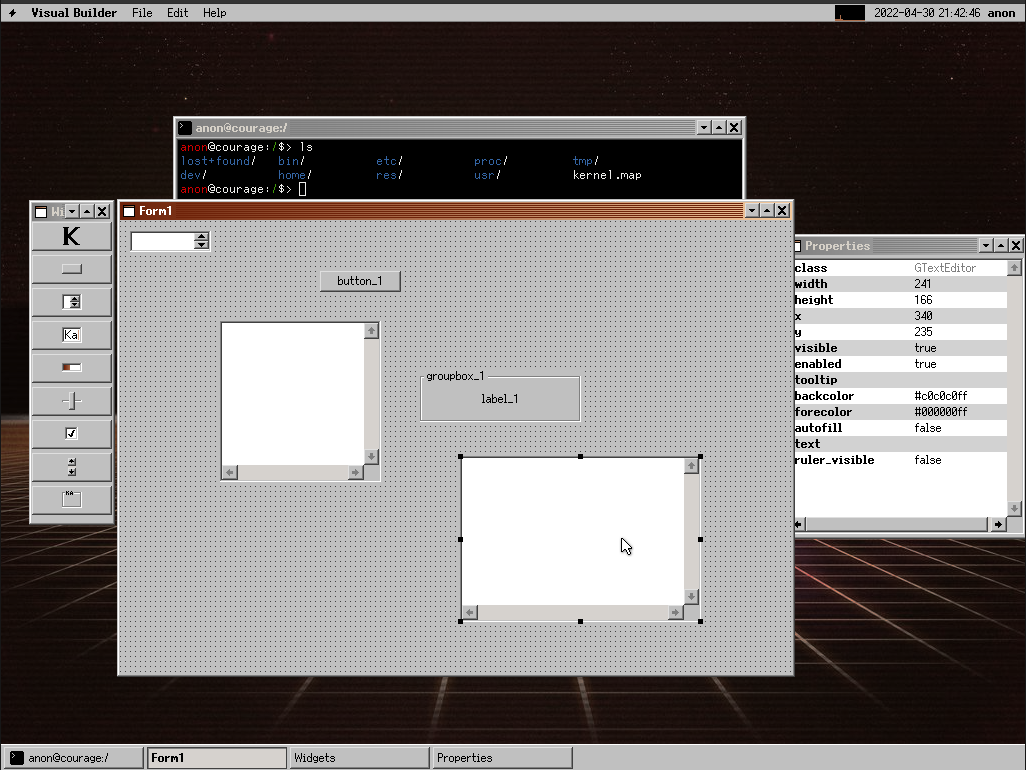

Running the build steps from this commit boots into an early, yet still familiar serenity QEMU window.

The one modification I had to make at this commit was to change the install target in LibC/Makefile to depend on all instead of $(LIBRARY). You can try it yourself on a linux system by checking out 612e1c7023e6b828e9d3d2746cd885e92d4f3f04 from serenity, installing the prerequisites from Meta/BuildInstructions.md, and running the build. The build steps required are:

sed -i "s/install: \$(LIBRARY)/install: all/g" LibC/Makefile

cd Toolchain

./BuildIt.sh

source UseIt.sh

cd ../Kernel

./makeall.sh && sudo run

That sure is a mouthful, isn’t it? Let’s go over what’s actually happening here. There’s really 4 steps to the build at this stage:

- Build the cross-compilation toolchain (BuildIt.sh)

- Build the Kernel and Userland C++ files (Kernel/makeall.sh)

- Install all the files into a sysroot, and build a root filesystem for Userland (Kernel/sync.sh, called from makeall.sh)

- Point QEMU to the Kernel binary and rootfs, and boot the system (Kernel/run)

These basic steps haven’t really changed much since May of 2019, but the details certainly have.

At this point in time, the basics of the toolchain build were already in place:

- Download and patch toolchain files. In this case, binutils 2.32 and gcc 8.3.0.

- Build binutils and gcc targeting

i686-pc-serenity - Build and install compiler support machinery (libgcc)

- Ensure LibM and LibC headers are installed into the sysroot for the build

- Build the C++ standard library (libstdc++) and install it into the sysroot for the Kernel and Userland to link against.

In the early days, the folks working on the Toolchain build didn’t realize that we don’t actually need to build the C library, Math library, etc. and only need the headers for the runtime library build. This was corrected later (2020 time-frame).

But wait, we can just download a version of gcc from our linux distribution’s package manager right? Why do we need to build the compiler and linker from source? The answer is simple to state, but subtle to explain: We need a cross-compiler toolchain that knows how to target serenity, and upstream gcc/binutils don’t know anything about serenity.

What’s a cross-compiler?

Before we go much further, it’s important to understand what a cross-compiler and compiler “sysroot” actually is, and why we need both of them.

When discussing compilers that produce native code, there’s three machines involved that may or may not be the same machine(s) in the end: the build, host, and target machines. These machines are conventionally described by their “target triple”. For example, my x86_64 Ubuntu 21.10 machine has a target triple as reported by gcc -dumpmachine of x86_64-linux-gnu. Note that the CPU architecture, OS Kernel, and C library API are all reflected in the target triple. If you change any one of the target triple parameters and try to execute the same binary, your binary will likely not work. An x86_64 binary won’t be able to execute on a Raspberry Pi (without qemu and binfmt-misc shenanigans). A binary dynamically linked against glibc won’t work on a musl-libc distribution like alpine. A binary compiled for SunOS won’t work on linux.

The rationale behind why an x86_64 binary won’t work on an aarch64 machine like a raspberry pi is straightforward: the binary format of the instructions is completely different. The encoding for “move the value from register 14 to register 15” is not going to be the same between different CPU architectures. If you do try to execute a linux x86_64 binary on a raspberry pi, you’ll likely get an error talking about an “exec format error”.

For different C standard libraries on the same operating system, it’s a bit different. If you link a binary against glibc and try to run it in an alpine container, you’ll get a mysterious “file not found” error. What this is actually telling you is that the requested program interpreter, the GNU ld.so, doesn’t exist on that system. If you did manage to force the musl program interpreter to load the application for you, you’d run into runtime symbol resolution errors. The exported symbols from glibc just don’t all exist in the musl C library.

The different OS case is a bit more subtle, so let’s look at an example. Suppose we want to build a simple application that prints the version of zlib installed on the system to the terminal. To build a “native” application, that is, an application compiled on the system we intend to run it on, we would invoke a native compiler.

To make it so that the serenity kernel doesn’t completely choke on the binary before trying to execute it, we’ll build it as a fully static PIE executable with clang and lld.

cat << EOF > ver.c

#include <zlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int, char**) {

printf("zlib version is %s\n", zlibVersion());

return 0;

}

EOF

clang -fuse-ld=lld -static-libgcc -static-pie -g ./ver.c $(pkg-config --libs zlib)

./a.out

On my ubuntu 21.10 system, this program prints “zlib version is 1.2.11”. Since we created a fully static binary, however, it is possible to run the binary on older or non-glibc distros, like centos-7 and Alpine respectively. For example:

$ docker run -it --rm -v $PWD:/example alpine /example/a.out

zlib version is 1.2.11

$ docker run -it --rm -v $PWD:/example centos:7 /example/a.out

zlib version is 1.2.11

This works because even though the dynamically linked C libraries on those systems are different and incompatible with a dynamically linked version of our “ver.c” program, the statically linked application only depends on the linux kernel having a stable userspace interface. And as Linus Torvalds is known to say, “We don’t break userspace!”.

On the other hand, what if we wanted to execute that binary on OpenBSD system? Or on serenity? The short story is, it doesn’t work. While both OpenBSD and serenity are unix-like operating systems that have ELF formatted binaries, their Application Binary Interface (ABI) with the operating system is incompatible with the linux kernel’s.

When trying to execute this binary in serenity, it crashes some time after trying to execute an unknown syscall. During the relocation processing that glibc’s static pie startup code is trying to do, it eventually gets to a point where some data that it really expected to be changed isn’t updated properly, and tries to write to a garbage address.

4.916 [#0 Shell(38:38)]: exec(./a.out): WARNING - Dynamic ELF executable without a PT_INTERP header, and isn't /usr/lib/Loader.so

4.920 [#0 a.out(38:38)]: Unknown syscall 158 requested (0x0000000015ec91b0, 0x0000000000003001, 0x0000000000000840, 0x0000000ca0edd790)

4.920 [#0 a.out(38:38)]: copy_from_user(0x0000002009f60b90, 0x0000000000000007, 24) failed at V0x0000000000000007

4.925 [#0 a.out(38:38)]: Unrecoverable page fault, write to address V0x0000000000000358

Hopefully this helps shed some light on why we can’t just run linux binaries on serenity. Their ABIs are incompatible. So then, how do we get the compiler to generate an executable userspace program that can run on top of the serenity kernel?

Let’s go back to the three machines involved in creating our compiler: build, host, and target. The build machine is the machine that holds the source files for the compiler, and uses a previous iteration of some compiler perform the build. In the example of updating clang, this is the machine that has the llvm-project repository cloned, and that will be performing the cmake && make dance to kick off the build. The host machine is the machine that will be executing the just-built compiler. Unless you’re doing a Canadian Cross, the build and host machines will be the same. In the llvm example, I’m building a compiler with a build machine of x86_64-linux-gnu, that will eventually run on x86_64-linux-gnu to create binaries for… some platform. That last part is the target machine. Where will the binaries that the new compiler produces be run?

To summarize, a cross-compiler is a compiler where the host and target machines for the compiler are different. If I want to build a whiz-bang IOT application for my raspberry pi, and do it in a continuous integration setup on github, I probably don’t want to have to hook up a build farm of raspberry pis to my github account to act as CI runners. Instead, I’ll install an aarch64-linux-gnu cross-compiler on my cloud runners to produce aarch64 binaries to run on my pi after the fact. The same is true for our serenity builds. We don’t have a physical machine laying around that is already running serenity with a compiler installed on it, so we need to create a cross-compiler that runs on x86_64-linux-gnu and produces binaries for i686-pc-serenity. Technically the serenity triple should probably be something like i686-serenity-serenity, but the name has stuck.

Now that we have an intuition for why we need a cross-compiler in order to create serenity userspace applications it’s time to build one. But not so fast, the compiler actually needs some help from us, the OS developers, to define what properties our target operating system has. If we want to build the C++ standard library (we do) for the compiler’s runtime support, we’ll need to tell the STL build what features and methods our OS’s C standard library has. This is where two related concepts come into play: Toolchain patches, and our OS sysroot.

Toolchain patches and sysroots

Toolchain patches are straightforward enough. The compiler and linker need to know that our operating system exists. In order to be able to build and link any userspace libraries or applications, the Toolchain components need to know what properties our runtime libraries like libc, libpthread, libdl, etc have. The Toolchain also needs to know whether the runtime supports dynamic linking, position independent executables, thread-local storage, and other output-format related options.

The OS sysroot requires a bit more explanation.

When doing a native compile where host and target are the same, the natural place for system includes is somewhere like /usr/include while the natural location for system libraries is somewhere like /usr/lib or /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ on a debian-based system. How does the compiler know where to look for the system headers and libraries?

The answer is a mix of hardcoded default paths, and Toolchain configuration. The Ubuntu-shipped gcc 11.2.0 was configured with options like --prefix=/usr, --libdir=/usr/lib and --libexecdir=/usr/lib. By default, the compiler and friends assume that all these prefixes and libdirs are relative to /.

What if we want to cross-compile though? The headers and libraries for the host are not suitable to include or link into cross-compiled applications. A sysroot, or “system root”, solves this problem. We create a sandbox directory that contains the normal Unix root directory structure underneath it, and drop our headers and system libraries in there. Instead of looking at /usr/include for <stdio.h> and /usr/lib for libz.so, we can instruct the compiler via --sysroot= to look in our sandbox instead. /home/me/sandbox/i686-pc-serenity/usr/include instead of /usr/include, etc.

Makefile build, explained

Going back to the original build steps for serenity, hopefully there’s now some intuition for what the first step is actually doing:

- Build the cross-compilation toolchain (BuildIt.sh)

- Build the Kernel and Userland C++ files (Kernel/makeall.sh)

- Install all the files into a sysroot, and build a root filesystem for Userland (Kernel/sync.sh, called from makeall.sh)

- Point QEMU to the Kernel binary and rootfs, and boot the system (Kernel/run)

After the toolchain is setup, it’s finally time to build the operating system.

The main build script at this point was Kernel/makeall.sh. The script itself is pretty simple. It declares all the build folders in a manual and copy-paste heavy manner, and then iterates over each folder running make clean and make. If there’s a script called ./install.sh in that folder, it executes it to install built binary artifacts into the sysroot (Root/)

Each Makefile is fairly straightforward. They include a common file, Makefile.common from the root of the repository that sets the default CFLAGS, CXXFLAGS, etc, Declare set of object files, an APP or LIBRARY target, and use standard makefile trickery to have common .cpp –> .o rules generated.

For example, here’s Demos/HelloWorld/Makefile:

include ../../Makefile.common

OBJS = \

main.o

APP = HelloWorld

DEFINES += -DUSERLAND

all: $(APP)

$(APP): $(OBJS)

$(LD) -o $(APP) $(LDFLAGS) $(OBJS) -lgui -lcore -lc

.cpp.o:

@echo "CXX $<"; $(CXX) $(CXXFLAGS) -o $@ -c $<

-include $(OBJS:%.o=%.d)

clean:

@echo "CLEAN"; rm -f $(APP) $(OBJS) *.d

At this point in time, there were only four libraries: LibC, LibM, LibCore, and LibGUI. And AK, the standard library, whose objects were (and still are) linked directly into LibC and the Kernel.

The simplicity of the build here enabled a developer workflow where the developer could rebuild the component(s) they were currently working on, while keeping the build familiar to Unix gurus. In Andreas’s Youtube videos from Early/Mid 2019, he’d frequently have commands like the following in the terminal history:

make -C ../LibGUI install && make -C ../TextEditor && sudo ./sync.sh && ./run

As a whole, the developer experience is simplistic, but comfortable to a certain kind of developer.

As the project matured and attracted more developers, however, the vintage feel of Makefiles and shell scripts started to fall short. The main issue was that as sub-projects like LibWeb and LibJS started picking up contributors and more and more files were added to the project, the lack of a partial rebuild solution was really dragging on build times.

However, the full conversion to CMake deserves its own post, so we’ll go over that in Part 2 :^).